Roots of Contemporary Conflicts, Part 3. Wild Fields

“Wild Fields” refers to the wide expanses of the Ukrainian and South Russian steppes between the rivers Don, Dniester and upper Oka, perhaps as far as the Caspian Sea. This region was barren for a long time. Various raid of nomads and other tribes prevented people from settling down in this area. In the 18th century, the Wild Fields were incorporated into the Russian Empire and renamed “New Russia”. Since the 16th century, Cossacks (among other settlers) had been building their fortified settlements in this territory.

Contents

Who Were the Cossacks?

The term “Cossack” is derived from the word cosac, which meant ‘free man’ but also ‘conqueror’. In ancient times, the Cossacks were more or less Slavic descendants, who lived as nomads in the steppes of Russia.

Historical records of the Cossacks are rather scarce until the 16th century. They were known as independent communities organized into “armies”, who were both fighting and cooperating with neighbouring states - primarily Moscow, Rzeczpospolita and the Crimean Khanate.

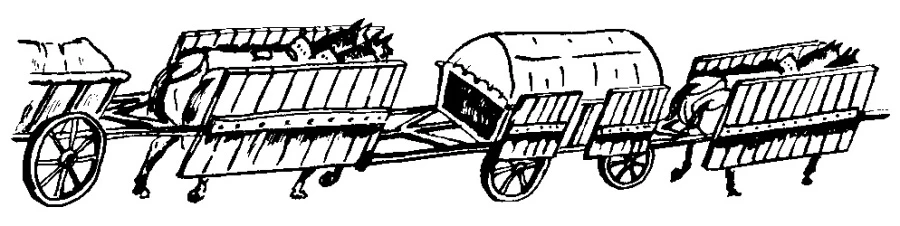

On the lower Dnieper, behind the rapids (behind the “porohy”), settled the Zaporozhian Cossacks (the present-day city of Zaporizhzhia literally means “beyond the rapids”), whose centre was Zaporozhian Sich. These settlers consisted mostly of infantrymen who protected themselves with a wagon fort - a “camp”. On their boats, chaikas, they launched raids and expeditions to the coasts of the Ottoman Empire. They rarely fought on horseback.

The Zaporozhian army grew rapidly: mainly thanks to runaway serfs from Poland and Russia, Tatars from the Crimea, and adventurers from all over Europe. Every candidate had to make the sign of the cross and say the Our Father and other prayers.

From the beginning of the 17th century, the Zaporozhian people considered themselves members of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth - the Rzeczpospolita. Their traditionally strong devotion to the Orthodox Church put them at odds with the predominantly Catholic leaders. So, when Bohdan Khmelnitsky started his Cossack uprising in 1648, they joined without hesitation, and gained considerable autonomy.

The “camp” (Edgar Pachta's archive)

War and Peace: the Complex Relations with the Russian Tsars

Some time later, Russian tsars began to be a threat to the Cossack “freedoms”. In response to the threat, the Zaporozhian army under Kosta Hordijenko joined the rebellious Ukrainian hetman Mazepa. After the Battle of Poltava in 1709, Peter I had the town of Sich destroyed. The Zaporozhian Cossacks then built a new centre on the Lower Dnieper, under the Turkish protectorate.

They made peace with the Russian government in 1734; they restored Sich, accepted escaped serfs from Russia and Poland, and refused to submit to autocracy. Sich was conquered again in 1775.

The Zaporozhian army had a distinctive military and administrative structure, and life in Sich was governed by specific customs and laws. For example, no woman was allowed to enter. Thieves were clubbed to death, and murderers were buried together with their victims.

In 1762, there were 33,700 Cossacks in Zaporozhye - who were, according to contemporaries, very fierce and difficult to control.

The Ukrainian Territory Since the 16th Century

From the 16th century, Ukraine belonged to the Rzeczpospolita, and was divided into 20 military districts. Each of these districts was to support the Polish-Lithuanian army with its own contingent in the event of war.

In 1654, Russia annexed 10 Ukrainian districts located on the left bank of the Dnieper. This part of Ukraine was then called “Little Russia” (Malorussia). At the end of the 18th century, when the Rzeczpospolita was divided, most of Ukraine was incorporated into the Russian Empire. However, by that time, the Malorussian Cossacks could no longer keep up with the modern military demands.

At the time of the Patriotic War of 1812, the Russian army was supported by four mounted Ukrainian Cossack regiments. They were reorganized into Uhlan regiments in 1817.

Russia in 1812: Ukrainian Cossacks of the 2nd regiment (Edgar Pachta's archive)

Cossack Weapons

The Cossacks considered their weapons to be treasures and handled them with respect. Although they adopted firearms at some point, they did not abandon their traditional cold weapons, which they considered more effective.

Polish Hussar sabre from the 17.- 18th century.

The sabre has always been a symbol of the Cossacks.

The nagaika was a short whip originating from the Nogay steppe. The main purpose of a nagaika was to urge a horse, however, it was also used in battles, when other weapons were not available. Sometimes, it was used together with a sabre, one weapon in each hand. According to Cossack tradition, nagaika was the first weapon that a warrior was given in his adolescence.

A spear, about 3 metres long, a weapon of simple construction, suitable for fighting on foot or from horseback. The Cossacks also used the spear to jump over muddy puddles in the swamps, and generally knew how to use it well.

Cossack mattock, or war hammer, was weapon used in the Middle Ages to break through armour. Some mattocks had a dagger hidden in the handle.

The Cossack mace. A blunt weapon with a short shaft and a head consisting of 6-7 blades. The mace was used as a symbol of commanding officers.

Firearms, arquebuses, muskets and pistols: Cossacks used the same firearms as other armies of their time, often acquired as trophies. The Zaporozhian soldiers are said to have started their day by drinking liquor and practicing firing their rifles at nearby birds.

The bow had long been used alongside firearms. This was mainly because it was more accurate, faster and almost noiseless.

A mace. One of many variants used at that time.

Cossacks did not use armour. In the 17th century, they wore a long tunics, originating from the Orient and introduced to Ukraine via Hungary and Poland. The tunics were made of home-woven woollen cloth in white, grey and brown; sometimes yellow-brown or green. Festive tunics were made of more expensive and more colourful fabrics.

In winter, they also wore a long cloak or coats to protect themselves from the cold.

Eastern-style trousers and boots covered their legs. The headdress was a papakha - hats made of sheep fur or even more expensive fur. Both Zaporizhian and Ukrainian people shaved their heads except for the hair on the top of the head, and wore long moustaches.

Hand-carved powder horn

The Military Elite: The Army of the Crimean Tatars

The Crimean Khanate did not have a strong economy, natural resources or numerous population (it had about 300,000 inhabitants), but it had one impressive thing: a powerful army.

A horseman from the East (SHŠ Cassanova, SK)

A willingness of soldiers to fight was moreover boosted by various factors, including propaganda. Archery and horse riding were essential parts of their training. The Tatars rode small but tough and strong horses. The psyche of the Crimean soldiers, the Askers, was harsh, their humour was black, their pranks bloody, and the people who fell victim to these did not always live for a long time.

Bows, arrows and sabres were the standard weapons. From the second half of the 17th century, pistols, carbines and spears grew in popularity. The poor warriors did not have sabres or even bows - they used homemade spears and maslaks (a horse’s jaw bone bound to the long pole).

The elite of the army was the Khan's Guard, consisting of 3-4 thousand soldiers. The most numerous part of the army was the Crimean Tatars and the Nogais. It was possible to increase the number of soldiers to ca. 30 thousand men. The army could further be reinforced by Nogai and Circassian troops.

The camp was set up in advantageous terrain, which offered drinking water and grazing lands. The Tartars rarely built fortifications. An important element of their warfare was the demoralization of the enemy: in the middle of the night, the warriors suddenly began to scream, and the terrible screams from thousands of men did not let the enemy sleep.

On the battlefield, the Askersentered the field with the sound of drums, in formations with flying banners. The warriors circled around the enemy ranks, searching out their rivals, fighting with their sabres and firing their bows and pistols.

Bashkir archers (KVH KP)

Their military operations required dexterity, good judgment and shrewdness, a little bit like a gambling game in which life was at stake, and their success was measured by the number of slaves and loot obtained. In general, contemporary sources praise the military potential of the Crimean Tatars. Until the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries, they were considered dangerous opponents.

The cover photo shows Zaporizhian Cossacks performed by the Cassanova group.

Comments