The History of Crusades - Part 2: The Rise and Fall of the Crusaders

Contents

Knights and noble ladies of the 12th - 13th century. Source: “The Costumes of All Nations“ (1882), illustration by Albert Kretschmer

Knights became the symbol of Western Christian virtues; and Constantinople with its magnificent walls became the symbol of the Eastern Church. Sounds nice! But history is full of paradoxes.

The Latin Empire

In 1204, Constantinople was afflicted by a huge disaster. Orthodox Byzantine Empire was conquered during the Fourth Crusade, and the Roman Empire was established there.

A Crusader knight at prayer. Source: E. Pachta

Many local rulers then submitted to the Franks of the Latin Empire, other regions broke away. The mixing of Eastern and Western cultures influenced the design of the armour and other parts of gear used by the warriors, many of whom came from the Crusader states from “beyond the seas”.

Latin domination, however, did not end the Byzantine Empire. In 1261, the Nicaean emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus recovered Constantinople from the Latin Empire and restored the glory of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire.

Twilight of the Holy Land

After the sacking of Byzantine Empire, several crusades followed, including the so-called Children's Crusade. It was not what is sounds like: It wasn’t a crusade of children (their parents probably wouldn’t have approved anyway), but a crusade of ordinary countrymen, called the “children of God”, led by a few religious fanatics. Those who survived the long journey, eventually ended up in the hands of Christian pirates and slave traders.

A battle of knights, a 13th-century illumination. Source: E. Pachta

The Ninth Crusade, sometimes paired with the Eighth Crusade, is widely regarded as the last significant military expedition into the Holy Land. It was led by future Edward I of England who replaced Louis XI of France at the head of the crusader armies.

The pious Englishman, however, had a relatively small army (of about 2,000 men), which was later joined by contingents from Antioch and Cyprus. It was clear to Edward that his army was not sufficient to defeat the large, well-organized armies of the Egyptian Mamluks.

Moreover, the lack of unity between Christians began to show - the Venetians and the Genoese openly traded with the pagans.

Christian Tatars

But Prince Edward had an idea. He asked for assistance in an unexpected place, forming an alliance with Mongols, or Tatars. The Mongols have spread their influence as far as the border of the Muslim world. And many of them were Nestorian Christians. Nestorianism was the Assyrian Church of the East that broke away from the Church of the Roman Empire in the 5th century and went its own way. The Mongols came to know the Christian doctrine through China, where missionaries from Syria began to spread the religion in the 7th century.

A recreation of a medieval Mongol warrior. Source: E. Pachta

Unfortunately, not even the Mongol contingent could defeat the extensive Muslim army, and Edward soon realized his efforts were futile. He negotiated a truce with the Muslim army, survived an attack of an Assassin, and returned to England in September 1272, and was crowned the king of England.

There was no next crusade after this. In 1291, after the fall of the fortress of St. Jean de Acre, the Crusaders evacuated their last strongholds in Tyre, Sidon and Beirut. The Holy Land was lost.

The coat of arms of the Grand Master of the Templars, who fell in the defence of Acre. Photo: M. Coupek/E. Pachta

The Teutonic Knights

As we speak about the Crusaders, we should not forget to mention The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, also known as the Teutonic Order.

Entering the order of knights was the “easiest” way for young men to become knights. This didn’t require them to travel the world, and they still got an opportunity to spread Christianity with the sword in their hand - but not in the Holy Land, but in the Baltic states. Much closer to home for most European Crusaders.

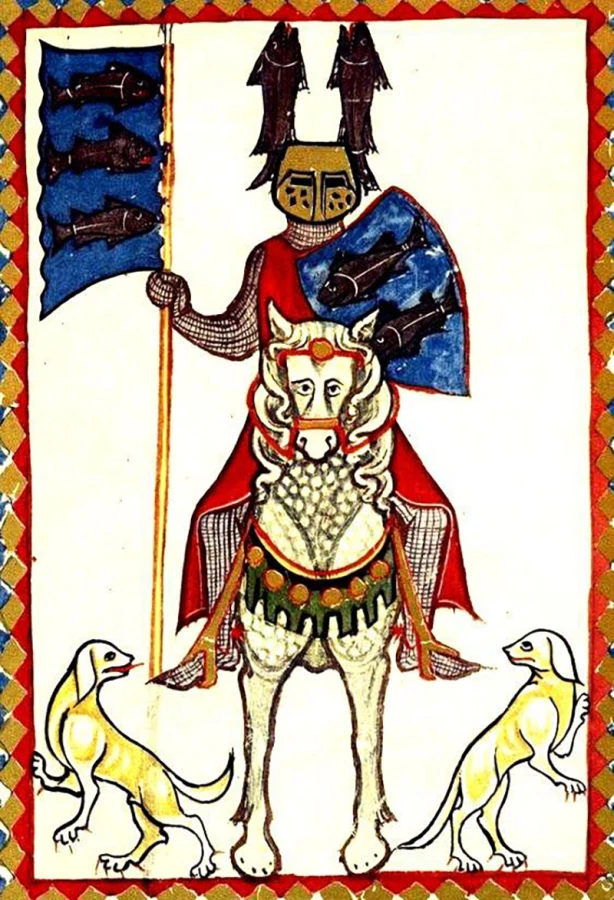

A knight from the early 14th century, Codex Manesse Source: E. Pachta

The Teutonic Order was formed at the end of the 12th century in the Holy Land. In the early 13th century, they helped to defend the eastern border of Hungary against the pagans; however, they claimed some territories, angered the Hungarians, and were eventually expelled.

Another challenge came in 1226, when Konrad I, Duke of Masovia, appealed to the knights to defend the borders against the pagan Prussians. Here in Prussia, the Teutonic Crusaders earned their own territories and formed a state that affected the future events in Europe. Around 1236, the order assimilated the smaller Livonian Brothers of the Sword. Together, they planned their own crusade against Orthodox Russian princes. Despite several defeats, the Teutonic Knights held regions in the Baltic area for a long time, and they still exist today as a charity organization.

The Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights (left) and the Livonian Knight of the Sword from the 13th century. Source: E. Pachta

Medieval Military Elite

Western European knight, re-enactment of the Battle of Bouvines (1214). Source: E. Pachta

The knight of the 13th century was already markedly different from the earlier versions of knights. Their garments incorporated contemporary fashion as well as more developed works of craftsmanship. Their gear included chainmail shirts, a hood and gloves, hauberk, and chainmail protection for the legs. The helmet gradually developed into the heavy great helmet covering the entire head.

Great helmet from the times of Crusades

The knights wore an armour with a sleeveless tabard over it. The horses of the richest knights were usually covered with a horse trapper, while the poor knights could not afford special accessories for their horses. The horse trappers provided protection to horses against the scorching sun of the Holy Land.

Knights did not travel alone. They were accompanied by servants, carts loaded with weapons, tents, food and other essentials. They also had a few warriors around as a part of their company. They had a war horse (destrier), which they only mounted for battles, and another horse or a mule for their daily journeys. A knight with a company was called lance fournie (‘equipped lance’), because lance was the weapon of first contact. The knights used shields for defence as well, but they were smaller, with a triangular shape.

A 13th century cavalry shield

Dubbing (Accolade)

The dubbing is a ceremony to confer knighthood. From the 15th century onwards, the lower nobility was allowed to use the title of “knight” without being dubbed. But until 15th century, every knight had to be dubbed to become one – whether he was a peasant, or a royal prince. In the dubbing ceremony, the candidate was usually tapped on both shoulders with the flat side of a knighting sword, and words were uttered, usually “In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, ...” or other words.

German tournament helmet with “jewels”, 13.- 14th century.

Around 1500, it was still the habit for boys from noble families to serve at courts of the higher nobility. Here, they were taught modesty and perseverance, proper manners and the rules of courtesy. They learned horse riding and fencing. When they were 15 years old or around, they were considered to be fully trained for their future tasks - their main task being the backbone of medieval armies. A dubbed knight was allowed to use their own coat of arms and enjoy various privileges, for which he was willing to risk his own life.

A medieval battle began with a charge of the knights, and soon fragmented into a series of duels between two knights. Most of the time, it was a bloody encounter, full of chaos and desperate deeds. Sometimes, however, there was no fighting at all, and the battle took form of plundering of the enemy's territory. Other times, the battle ended with negotiations of peace. Tournaments were a way of training for the knights.

A battle of knights, as depicted in the Maciejowski Bible. Source: E. Pachta

Deadly Weapons

Swords were until the 14. century the deadliest weapon on the battlefields. Severed limbs, rolling heads, destroyed armours... The reports from the medieval battles are not exaggerated. A skilled warrior was able to cut his opponent to pieces, quite literally. In 1272, in a duel between prince Béla and the Count of Kisek in Hungary, Béla was killed and cut into pieces, which, according to the chronicles, "the crying Hungarian princesses were then collecting".

A recreation of heavy infantry with two-hand weapon and an iron helmet, 13-14th century 13th century. Source: E. Pachta

Comments